[ad_1]

The documents, obtained by TN BJP chief K Annamalai through an RTI application, bring out Sri Lanka making up for its lack of size with tenacious pursuit of the 1.9 square km of land about 20km from Indian shore based on claims which New Delhi contested for decades only to acquiesce to finally. Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, pressed its claim right after Independence, when it said Indian Navy (then Royal Indian Navy) could not conduct exercises on the island without its permission. In Oct 1955, Ceylon Air Force held its exercise on the island.

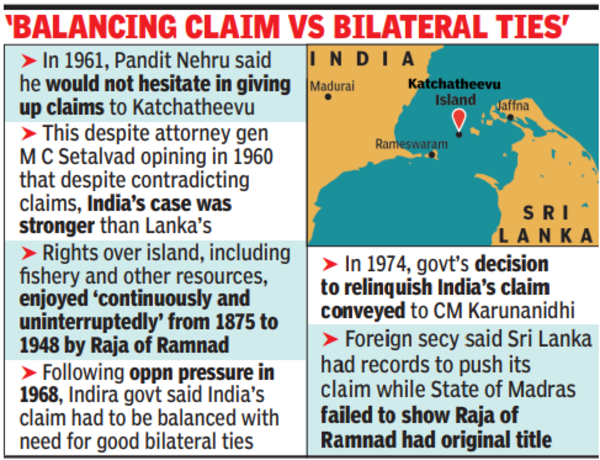

Its stance was reflected in a minute by first PM Jawaharlal Nehru on May 10, 1961, who dismissed the issue as inconsequential.

I would’ve no hesitation in giving up claims to the island, Nehru wrote

I attach no importance at all to this little island and I would have no hesitation in giving up our claims to it. I do not like this pending indefinitely and being raised again in Parliament, Nehru wrote.

Nehru’s minute is part of a note prepared by then commonwealth secretary Y D Gundevia, and which the ministry of external affairs (MEA) shared as a backgrounder with the informal Consultative Committee of Parliament in 1968.

The backgrounder is revealing in terms of the indecision that marked India’s response until 1974, when it formally gave up its claim altogether. “The legal aspects of the question are highly complex. The question has been considered in some detail in this ministry. No clear conclusions can be drawn as to the strength of either India’s or Ceylon’s claim to sovereignty,” the ministry said.

This, despite the opinion of the then attorney general M C Setalvad, in 1960, that India had a stronger claim on the island formed by a volcanic eruption. “The matter is by no means clear or free from difficulty but on the assessment of the whole evidence it appears to me that the balance lies in concluding that the sovereignty of India was and is in India,” wrote the well-regarded law officer in a clear reference to the zamindari rights given by the East India Company to Raja of Ramnad (Ramnathpuram) over the islet and fishery and other resources around it.

The rights enjoyed “continuously and uninterruptedly” from 1875 to 1948, which got vested in the State of Madras after the abolition of zamindari rights, were exercised by the Raja independently, without having to pay tributes or taxes to Colombo.

The documents show that MEA’s own joint secretary (law and treaties) K Krishna Rao was not sure, but concluded that India had a good legal case which could be leveraged for securing fishing rights – the cause for the continuing ordeal of hundreds of Indian fishermen who are detained by Sri Lankan Navy, around the island.

While observing that Colombo’s claims are more “substantial”, in 1960, Rao wrote: “On the other hand, it may be noted that India has a good legal case, which could be argued with considerable force. I am not suggesting that we have no case at all.”

Even Gundevia, who did not consider the uninhabited island, with only a church on it, to be “really important”, was against taking the risk of having to give it up, the MEA told the consultative committee in 1968.

The same year also saw the opposition taking the Indira Gandhi govt to task for its apparent unwillingness to confront Sri Lanka as it doubled down on its claim over the island.

In a discussion in Parliament, they demanded and got a discussion against the backdrop of rising suspicion about a deal being secretly negotiated between Indira Gandhi and her Ceylonese counterpart Dudley Senanayke during the latter’s 1968 visit for handing over the island. Opposition members chided govt for not standing up to the signs – statements of Ceylonense PM Senanayake in their Parliament and of local functionaries, Katchatheevu being shown as their territory in maps – as creeping acquisition of the island.

The Indian govt denied that the island has been signed away but emphasised that it was a disputed site and that India’s claim had to be balanced with the need for good bilateral ties. The response by Surendra Pal Singh, deputy minister in the MEA, that the island was uninhabited appeared to remind socialist veterans such as Madhu Limaye and Rabi Ray of Nehru’s “not a blade of grass grows” remark after China’s annexation of Aksai Chin, who flew into a rage.

Opposition raised the matter forcefully again in 1969, but the two sides continued to inch towards an agreement which would concede Sri Lanka’s claim.

A year after foreign secretary-level talks in Colombo in 1973, the decision to relinquish India’s claim was conveyed to Tamil Nadu chief minister M Karunanidhi in June 1974 by foreign secretary Kewal Singh. The meeting saw Singh mentioning the zamindari rights of Raja of Ramnad as also the failure of Sri Lanka to produce any documentary evidence to prove Lankan holding the title to Katchatheevu.

However, the foreign secretary emphasised that Sri Lanka had taken a “very determined position” on the basis of “records” showing the island to be part of the kingdom of Jaffnapatnam, Dutch and British maps, the acceptance of an Indian survey team of its claim and the failure of the State of Madras to show that Raja of Ramnad had the original title.

He said that Ceylon had asserted its sovereignty since 1925 without protests from India and cited a second opinion of 1970, by the then attorney general that “on balance, the sovereignty over Katchatheevu was and is with Ceylon and not with India”.

Singh sought immediate concurrence from Karunanidhi, citing internal compulsions – India finding traces of oil that Sri Lanka was then unaware of, and external ones like the growing presence of pro-China lobby in Colombo and govt’s reluctance to move the World Court, arguing that it tends to favour smaller countries. The foreign secretary did not have to press hard.

Part 2: DMK’s stand

[ad_2]